Loudness in mixing explained

By Rob Stewart - JustMastering.com

If you are reading this now, you may have been looking for mastering loudness tips, or even a mastering engineer that practices "loud mastering". If you are eager to learn what you can do to make the loudest, most dramatic mixes possible, then set down that maximizer, remove that limiter, and read on :).

I regularly address the issue of loudness in my practice, and because of that, there are some key things about it that I am compelled to share. If you are working on a mix right now, are considering self-mastering, or paying to have your music mastered, you will no doubt consider loudness at some point during that process. This article is just barely scratching the surface of loudness, but I hope that my thoughts help you create more musical and engaging recordings.

We are at an exciting time for audio. The so-called "loudness war" has been reduced to a mere "loudness disagreement". There is a growing movement to move away from "hot" (high gain) masters, returning music towards more conservative gain levels. From my perspective, this movement has been led largely by audiophiles and the independent music industry because of their often high focus on sound quality, but we are starting to see more change in the broader industry as well. Technologies like Apple's "Sound Check" are in wider use (for example, on iTunes radio), and other loudness normalization technologies may soon be part of your average Hi-Fi system. What a great time to be involved in music!

What is loudness?

We could spend several days talking about the topic of loudness, but in short:

- Loudness is a trait or quality that we subjectively apply to sound based on how we perceive its level of strength.

- Loudness is often perceived relative to something else.

There you have it. That is as succinct as I can be :)! You can read much more technical detail about loudness here.

Because loudness is perceived - and is subjective, any recording, mix, production or mastering decisions you make to enhance loudness need to take listener perception into account. That is to say, do not confuse loudness with high gain levels in a recording, or high SPL (Sound Pressure Level) on playback. Gain and SPL are both objective measurements. Loudness on the other hand, is both subjective (perceived by the listener) and relative (compared with something else).

Here is an example. Music played at a low SPL in an empty restaurant sounds just right to the owner, but suddenly becomes masked by various noises as the room fills with more and more people. The staff will then turn the music up a little to make it louder, relative to the room noise, so that it can be heard. Soon, the crowd finds it harder to have a conversation (competing with the music) so they talk louder, further masking the music, so the staff may opt to turn the music up again at different points of the evening. If that continues, visitors arriving later in the evening find themselves walking into a very noisy room compared to the quiet street they just came from! On the flip side, most of the people who had been in the restaurant awhile did not notice it getting gradually louder and louder so they might be just as surprised to find their ears ringing after leaving the restaurant.

Key Loudness Concept:

Gain is meaningless on its own if you are using it to enhance loudness. To truly be heard, or perceived as "louder", you need a relatively stable baseline reference point for the listener to compare other "louder" sounds back to.

If higher gain is not enough to make my mixes loud, what makes us perceive sound and music as "loud"?

Use Contrast to Maximize the Loudness of Your Mixes.

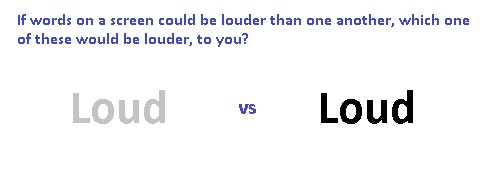

Our brains are constantly comparing differences between one thing and the next. It is how we are wired, and it's not just our hearing, but with all of our senses. It is automatic, and it is what allows us to perceive the physical world around us. Bearing this in mind, contrast is what makes certain things stand out against other things in the environment. Think of black text on a white screen. If we make the screen brighter or darker, we are adjusting gain settings which increase or decrease light output. In audio, that is like adjusting gain to raise or lower SPL. Now, if we replaced the black text on white background with grey text on a white background, we would effectively be reducing the contrast of what is on the screen, and it may make that text a lot harder to read as a result. In most situations, adjusting the gain to brighten or darken the screen would do relatively little to improve readability because you're adjusting the background and the text, together - that is, raising the gain does not increase contrast (unless there's something unusual happening with the monitor, that is!).

Where does contrast come from in audio? It comes from several places. Tonality (low frequencies can contrast with high frequencies), timing (an 1/8th-note triplet hi-hat pattern over a quarter note kick pattern), and dynamics.

Let's look at tone, first. Think of things that sound loud to you - a dog's yelp, a car horn, a baby's cry, a snare drum, bag pipes, etc. What do they all have in common? They all contain a large component of sound energy in a region that our ears are most sensitive to, relative to the rest of the audible spectrum - say roughly between 600Hz and 6kHz. Quite simply, the more energy a sound contains that is in that region, relative to other areas of the spectrum, it will typically sound louder to our ears than other sounds. Also consider the environment you hear it in, though. A barking dog sitting in a crowd of screaming people could be as loud or louder as it would be on its own in a quiet yard, but because of the environment it is in, you might barely notice it among all those people!

Even things like Thunder, or a kick drum sound big and loud to us because of the area of the spectrum that they occupy. Using Thunder as an example, we perceivea big house-shaking "boom" when lightening strikes because the sonic boom that is created by the lightening bolt creates a powerful shock wave that can be heard for miles. A large portion of that shock wave is low frequency (bass) information which travels longer distances than higher frequency sounds, however, a significant portion of the thunder clap is also in the midrange and even treble regions. In other words, we often remember the boom of the thunder the most, because the bass tends to echo and linger but what makes the thunder truly loud and powerful sounding is that it is largely a full-spectrum sound, with plenty of midrange energy which our ears are particularly sensitive to, which creates a real "crack" - particularly when that lightening is overhead, or very close by.

Timing can potentially play a role in loudness. For example, you can use delays less then 20ms to thicken a sound and make it appear louder. Take a snare drum, pan it hard left, run it through a 10ms delay and pan the delayed version hard right, then adjust the gain of the left channel downward a bit until the snare sounds centered. You now have a much thicker, and louder snare drum (just adjust the delay to taste). This is an old technique and it works on all kinds of instruments. Be careful of mono compatibility, and remember what I said about contrast, above (i.e. don't apply it to every track, or you'll lose contrast!).

And then with dynamics. Remember my black vs grey text analogy above? You could compare the range between white and black on a screen to dynamic range in audio. By making the text grey instead of black, you have effectively reduced the range of brightness (i.e. dynamic range) of what you're seeing. That reduced contrast caused by choosing grey text over black will impact of the text because the difference between grey and white is not as stark as it would be between white and black. Getting back to sound, thunder serves as another great example because that initial "crack" created by the sonic boom is relatively short in duration, but it's extremely loud. What follows is a relatively long decay that is at a much lower SPL, but we perceive thunder as loud (sometimes very loud!). Our brains process the loudness of the crack before we can react to the sound of the thunder. By the time we realize what caused the loud bang, we are left only with the lingering, echoing "boom" as the thunder fades away.

How do I apply these concepts to my music? How do I make my mixes louder?

Remember my #1 loudness tip above (contrast), while keeping these key things in mind:

- Loudness is perceived by the listener based on how sound is presented to them.

- Loudness, for the listener, is relative to other sounds in their environment.

- Loudness perception is directly related to frequency, timing and dynamics.

- Perceived loudness in your mix depends completely upon the source instruments, the raw capture (recordings) of those instruments, and how you arrange and mix them.

Loud instruments, and loudness in arrangements

Similar to the barking dog, or baby's cry that I mentioned above, some instruments are very soft, whereas others are naturally very loud. Snare drums are typically very loud, as are bagpipes. In fact, both instruments were designed to be heard from miles away. A classical guitar (depending on how it is played) can be a very quiet instrument. Even a piano can be "voiced up" to make it brighter (and louder), or voiced down to mellow the tone. When arranging and producing music, it is therefore extremely important to choose instruments and voicing very carefully. If you choose too many instruments that fall within the same tonal range, or even if you have the right instruments but they are playing in the same range too frequently, you will lose tonal contrast, which impacts perceived balance, and loudness.

Loudness in audio recording

Moving on to the recording stage, the recording engineer needs to choose the microphone, microphone placement and other pieces of the recording chain very carefully. A dull sounding microphone, or even a clear microphone in the wrong position during recording can create a really dull or dead sounding source recording. That will ultimately make the mix engineer's job challenging. Don't get me wrong, mix engineers are able to do some amazing things, but, there are limits. If clear, loud, vibrant and dramatic mixes are your goal, you have to put as much effort as possible in at the recording stage to ensure your source recordings are clean and clear.

Relative loudness in audio mixing

Loud sounds will sound louder when the listener has something to compare them to. Bearing this in mind, craft mixes that have a wide range of dynamics. Set the main mix elements (bass, vocal, etc.), low enough in the mix that the attack portion of the more dynamic instruments (drums for example) are well above them. This takes a lot of skill to do correctly, because you still have to set the drums at a level where they do not sound "too loud" for the song.

Pay attention to the spectral content of every mix element, and create tonal, timing and dynamic contrast between the elements that you want to sound loud, compared to the others. For example, if you want to create a loud vocal that stands well in front of the other mix elements, it must contain a very strong midrange component in the region where our ears are sensitive to. It also needs to have more of that midrange energy, relative to the other mix elements though. You can create that sense of contrast by mixing the guitars with less midrange energy than the vocals.

I will go back to dynamics again. Remember that the relative dynamics of thunder create that sense of loudness. A loud vocal therefore, should also be very dynamic! Though some genres historically call for a very compressed vocal sound, it is not necessary for creating a loud and dramatic mix, in fact it is often very damaging, to compress all of the attack notes of a strong lead vocal.

Key questions to ask yourself when approaching a mix:

- If I am aiming for a loud and dramatic mix, are my source recordings naturally loud (dynamic, clear, high contrast)? If your answer is "no", it is well worth revisiting the source recordings to see if there is anything that can be done - even if it means re-takes. Source tracks that are dull, muddy, or without any dynamics will make it extremely difficult for you to coax convincing and musical loudness out of them at the mix stage.

- Am I using compression to "glue" my mix together, or other indirect reasons? This is a common pitfall. If you are finding that you need a compressor on your mix buss, it could be because you haven't spent enough time on your mix. Don't get me wrong. Compression is a great thing, and it can be used to create dynamic contrast. The key is using it selectively. Use it when you need to reduce the dynamics of a mix element, but try to avoid it unless it's absolutely necessary. Mix compression is absolutely fine as well, as long as you are aware of how the compression is affecting perceived loudness.

Key Related Topic:

Check out the the Dynamics section of my "Mix Tips" article, that explains the "Attack Principle" - preserving or enhancing the attack portion of a mix element actually makes it sound louder, allowing you to sit it a little lower in your mix!

Mastering Loud - The fallacy of using heavy limiting and "loudness maximizers"

So you have spent months laboring over a mix, and it sounds absolutely perfect to your ears, it just isn't loud enough. Time to send it off for mastering, or run it through your favorite maximizer or limiter, right? Wrong!

Limiters and maximizers are extremely popular tools for many home recordists. I would be lying to you if I said that they were not used by professionals as well. *How* they are used is often quite different, though. Limiters were created to control transients to a degree. Careful transient control allows you to add what many refer to as "punch" (a whole other topic for future discussion), but over usage only degrades the sound quality of your mix.

Using a limiter to increase the loudness of your mix is, therefore, a trap. Do not be fooled into thinking that your meters are telling you that your hot mix is "loud". All you are doing is raising the gain of your mix. If you heavily limit your song, you will be able to increase the gain of the music, which may seem like you are making it louder, but remember that gain is an objective statistical measurement for audio (Key Loudness Concept above), whereas loudness is based on a listener's perception. It is fallacy to use a limiter to boost loudness. Doing that will damage important transient details in your mix which, ironically, would have helped make it sound louder! By damaging those transients you actually risk reducing musical impact and perceived loudness (adding significant distortion in the process).

Maximizers are all different from one another depending on how they are constructed. Some rely heavily on limiting, others use a combination of limiting, compression, equalization, and who knows what else. It is the who knows part that you need to be concerned about. Using a maximizer is fine as long as you can objectively assess what it has done to your sound, and you feel that change is a musical improvement. Heavily using a maximizer, or using one blindly (using presets for example), can do a great deal of damage to that mix that you worked so hard to create. If in doubt, I suggest leaving it off.

In my experience, enhancing loudness at the mastering stage is very difficult to do if the source instruments, recording and mix are not of high clarity, with wide dynamics to begin with.

Audio Mastering Myth: Mastering is not gain maximization

Audio Mastering is about maximizing impact, musicality and quality, not maximizing gain. A good mastering engineer will point out if your mix has issues that will impact its perceived energy or loudness, and they will recommend changes to your mix to enhance how listeners will perceive it.

I often use the term "loudness optimization" because certain songs, and genres, call for different levels of perceived loudness. Fast Heavy Metal music should be perceived as "louder" than slow Jazz for example! A good mastering engineer can tell you how you have mixed your song - if you have mixed it to sound quiet relative to the genre, they can suggest changes to help with that.

Pure audio mastering tools (EQ, limiting, compression and others) can do relatively little to make your mix louder, without compromises. It is best to address musical energy, impact and loudness right at the source. Clear, dynamic recordings that are part of a clear, dynamic and dramatic mix are the foundation of high impact music. That is precisely why top mastering engineers spend a great deal of time consulting with their clients about improving their mixes, first.

remember: the listener has the ultimate control

Key Loudness Concept #2:

To create a loud mix, you need to create a listening experience that encourages the listener to "turn it up"

It sounds obvious at first, but it is easy to forget that no matter what you do to enhance loudness in your mix, the listener makes the final decision as to how loud your music is in their environment. This is important. If you approach loudness in the wrong way - for example, by relying on heavy limiting to boost the gain - the listener will likely respond to that by simply turning the volume to a level that sounds right to their own ears which completely reverses what you did with the limiter!

The same applies to true loudness enhancing techniques. The midrange of a mix is absolutely critical, and it is a challenge to get right without an accurate monitoring system. Too much emphasis at the wrong frequencies will make a mix sound "too loud" or too harsh. Once again, in response to that, the listener will promptly turn your music down.

I mentioned loudness normalization (Apple's "Sound Check" for example), at the top of this article. An important note about loudness normalization is that it is doing the "control" job for the listener. It is not a perfect technology, but essentially it will adjust the gain of loud mixes down, and quiet mixes up. Therefore, it is futile to use a limiter to boost the gain of your mix for the sake of loudness, because if Sound Check is turned on, it will turn your mix down for the listener.

Bearing all of this in mind, I suggest not making loudness your primary goal when you create a mix. Instead, make crafting a compelling listening experience your goal. Go for quality, go for clarity. Consider the song, consider the genre, and consider how much impact you want to create in your mix. If you place the highest priority on musicality and impact, you will craft engaging mixes that will cause the listener to "turn it up", which is exactly what you want!

Key question to ask yourself before you touch that mix maximizer or limiter:

Am I planning to use this tool to compensate for a mix that has poor quality source tracks, or in place of taking the necessary time to create a compelling listening experience? If your answer is yes, I recommend tossing the maximizer and revisiting your mix. It will take a lot more effort but your listeners will thank you for it :)!

A word about "Loudness Units Full Scale" (LUFS) Loudness Metering

There is a relatively new unit of measure called a "Loudness Unit" that attempts to allow us to measure perceived loudness (yet another future topic!). It is not foolproof, but it is a great step in the right direction. Using a loudness (LUFS) based meter during mixing is a great idea to a point, but, I suggest using it more as a tool to confirm the level of perceived loudness, rather than "mixing to it" (aiming for a target on the meter). Instead, consider the key points I mentioned above about loudness, and incorporate those into your mixes. If you do that, you will come closer to creating dynamic, musical, exciting, and (when necessary) loud mixes!